I started reading The Body is Not An Apology (TBINAA) by Sonya Renee Taylor, thinking it would be just like every other body positivity book; the author, though well-meaning, imploring their readers to accept who they are, while often neglecting to include the experiences of marginalized bodies. However, I read TBINAA feeling like I had finally read something that not only addressed different types of people but gave me the confidence to start my own journey to radical self-love, as Sonya Renee Taylor calls it. Taylor does not promise that reading her book will instantly free you from the years of body-shame you’ve endured, in fact, she points out to readers that it will take patience and hard work to achieve.

Radical self-love, the term that Taylor uses in place of self-love, is the idea that we are inherently already enough the way that we are. Radical self-love requires us to see ourselves as people with intricately bound identities and creates a safe place within ourselves for those intersections. In contrast to self-love, “using the term radical elevates the reality that our society requires a drastic political, economic, and social reformation in the ways in which we deal with bodies and difference”. Radical self-love does not just involve us, but it constitutes a world in which all bodies can be valued and freed from oppression.

Each of us quickly learned what parts of our identity, if any, were accepted by society, and suppressed pieces of our identities that we knew would be criticized, according to Taylor. We were taught to rank ourselves among one another, placing our value on the greater or lesser value of others. Furthermore, these acts of oppression and shame projected onto our intersectional bodies is what Taylor calls “Body Terrorism”. We experience body shame everyday by media, political, and economic systems. Body terrorism isn’t a new concept, but instead a lived experience of many people in the past and present, she explains. The division of ourselves into social structures is used to both value and reduce our bodies. Taylor says that at young ages, each of us involuntarily learned body terrorism—implicit bias— without the consciousness or control in what we learned. None of us desires to have bodies that are different from how the default body is portrayed. Consciously or unconsciously, we adopted the language of fat-phobia and body-shaming.

Feelings of inadequacy and exclusion cause many people with disabilities to feel the need to apologize for their bodies. Taylor recalls in her book the interaction she had with her friend, Natasha, that inspired the TBINAA movement. After Natasha, a woman with cerebral palsy confided in Taylor about a sexual experience, Taylor uttered the words “Natasha, your body is not an apology. It is not something you give to someone to say, ‘Sorry for my disability.’”

Taylor says Natasha is no different than the rest of us, and that we have all been exposed to societal expectations of what our bodies should be and look like. Natasha, like many other people with disabilities, felt that because her body was not the default body type. she didn’t have the same rights as others. She was a victim of the ableism fed to her by societal pressures.

Body terrorism and body-shame are projected onto the bodies of disabled individuals that create misconceptions about disability and sexuality. Delete the following sentence – Not all disabled people are asexual, the same as not all able-bodied people are straight. People with disabilities experience love the same way that people without disabilities experience love, and according to Taylor disabled people practice radical love by celebrating the networks of care their community has used throughout history for survival. The community, including people of color with disabilities, has organized to challenge the systems of body terrorism. They have worked on changing the ableist ideas about people with disabilities as either inspiring or sad. The disability community has been one of the most persistent examples of “what it means to leave no body behind, and that care work and radical self-love are inextricably bound.” Love is not reserved for one group of people. Love is for all of us, Taylor shares.

If you are reading this article as an able-bodied individual, I implore you, step out of your comfort zone. Ask the difficult questions. Try to understand the experiences of disabled bodies. For all bodied persons, practice radical self-love and become a champion of every body. Because as Taylor says, “even a small wrinkle in the bed of privilege is enough to force some of us awake. It is in our awakening that we accrue the collective power to bring into being a transformed world predicated on radical, unapologetic love.”

Citations:

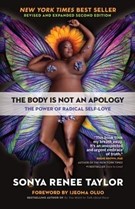

Taylor, Sonya Renee. The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love.

Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2021.

Explore the Body is Not An Apology website.

About the Author

Sydney Lumpkin is an intern for Tennessee Disability Pathfinder this

summer from her home in Arkansas, and attends Sewanee: The University

of the South. Sydney is expected to graduate from Sewanee in 2025, double majoring in Politics and Women and Gender Studies, and minoring in History. Outside of her studies, Sydney enjoys traveling, reading, and snuggling with her labradoodle.